Climate Label

Data gone wild.

The label is an important part of food products, which producers use to communicate their product’ characteristics to persuade consumers at a trading activity. The information on the product label often reflects and responds to the customers’ demands at a time. With the uprising public concern about the environmental aspect of food products and production in recent years, the question of the need for a climate label is unavoidable. In this essay, reports and literature will be reviewed to answer and discuss the raising question.

In the modern world, consumers are provided with a fruitful amount of food choices due to technological advancements and the free market. Their consumption behavior is no longer determined solely by the availability of food to serve basic nutritional needs1. A wide range of foodstuff options allows the customer to make purchasing decisions not only to satisfy fundamental demands but also to reflect their lifestyle and beliefs2. Consequently, policymakers and food producers need to understand population demands towards foodstuffs to perform corresponding strategic approaches at their challenging positions. Concurrently, policymakers need to keep benefiting their citizens, and producers to stay relevant in their business as society progresses.

Under the customer-centered market, food producers utilize product labels as a response to consumers’ demands in trading activities without their preliminary consumptions3. Thereupon, packaging has dual functions of protecting the food inside as well as conveying information from producers to consumers. The information existed in the product label can be mandatory, as an obligation to the officials’ regulations, or non-mandatory as a producers’ endeavor to persuade consumers to buy a product. Consequently, despite differences in legal status, this information functions as a cue to help customers making purchasing decisions depending on their preferences with certainty and willingness. For example, from 2014, European food producers are obliged to list potential allergens that existed in their product in the product label4. This implementation indirectly clarifies consumers’ questions about how their health preferences would react to food products without actually trying. In a different circumstance, the voluntary addition of an organic production label assures consumers the product is associated with organic production. As such, consumers could consume according to their opposition towards GMOs, or preference toward nature with certainty.

In the modernity theory frameworks of consumption and production, the modification and implementation of product labels mentioned above is a part of the producer’s business restructure in correspondence to customers’ demands. Therefore, new customers’ demands - which are formed by new societal ideology at the time - indirectly require new product labels, either mandatory or voluntary. For example, genetically modified food was introduced to the European market as early as 1996. However, only until consumers’ confidence in science and technology started to impose an uprising contradiction GMO, European Commission released their official regulation toward food producers on the issue in 20035. From then, European producers need to put GMO are required to put GMO labels onto their products if it is associated with genetic engineering technology to any extent.

Meanwhile, the environmental aspect in food and food production is gaining more recognition from the European public in the last decades. Consequently, this aspect would potentially become the determining factor of the customer in their consuming activities in the future6. Therefore it is inevitable to suggest the addition of climate labels to food products, based on a certified and quantitative system, in response to the uprising customers’ demands from this time on. In fact, as of now, several food companies have already implemented different versions of climate labels to their products such as Oatly, Estrella, Quorn7. Together with marketing strategies, their business gained exponential growth in the last few years. This observation alone not only suggest the producers’ need to adopt climate label for future business but also signify the needs of a mandatory one from policymakers to help their people avoid confusion while making a purchasing decision.

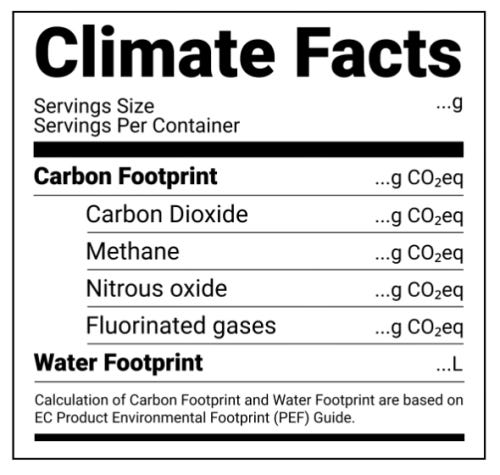

The above reasoning suggests that the implementation of the mandatory climate label in the food industry is certain to happen. Two fundamental characteristics of this label can be predicted based on both current mandatory labels and voluntary climate labels. Firstly, it would be a quantification label like a nutrition label instead of an identification label like a GMO one. In reality, any production activity has its environmental impact, and more often, it is the most effective technology available for producers. Besides, laws and regulations are not higher and are conditioned by the development of technology as society progresses. Therefore, considering foodstuffs is environmentally good or bad may do more harm to the society than benefit them, which the purpose of the implementation. Secondly, it would cover the environmental impacts of a product in more than one aspect (figure 1). As such, different product from different production technologies which require different resources can be evaluated indifferently by the regulations.

For customers, the implementation of such a climate label implies few foreseeable benefits. Firstly, it satisfies customers’ demands for a more environmentally friendly way of food consumption by giving them a tool to compare between products. Concerns about how their consumption behavior would impact the environment are resolved, paving way for more certain and enjoyable trading activities. Though this resolution is not the ultimate one because any production activity has its environmental impact, it would be the most effective tactic available. Secondly, the implementation helps customers consume at ease by guiding them through a matrix of voluntary climate labels in the market in the present. More often, these voluntary climate labels consider environmental aspects from different perspectives - namely carbon dioxide emission versus food milage. They are incomparable to each other. Consequently, consumers have been left with confusion while shopping, though their needs are responded to by food producers. In contrast, the implementation also suggests an obvious drawback for consumers.

For producers, the implementation is both the opportunity and the challenge for their businesses. A study conducted for the Swedish market suggests that consumers would pay more for food products with less GHG emitting8. Concurrently, Oatly, who has gained exponential growth in the last few years, famously adopts carbon dioxide emission number per product on their units and publicly promotes every producer to follow their paths. Though these case studies do not represent the whole European market, it suggests that climate labels can be used as a critical selling point for consumers in the future. On the other hand, the implementation forces them into a new technology race towards the most environmentally friendly production technique - which might remove small-cap companies. Moreover, it would also impose a challenge to businesses whose exporting foodstuffs as explained in the above paragraph.

To conclude, the need for a climate label in food products is inevitable and certain to happen in the future. It is because of the uprising importance of environmental aspects in consumers’ quality evaluation and the function of the product label is the producers’ responses to consumers’ needs. The future climate label would assemble fundamental characteristics of current mandatory product labels as well as voluntary climate labels circulating in the market. Furthermore, the implementation imposes more benefits than drawbacks to customers who consider the environmental aspect as the most determining factor in purchasing activities. Concurrently, producers would consider the implementation is both a challenge to their business structure and an opportunity to grow by new market demands.

Figure 1: Example of climate label based on nutrition label and voluntary climate labels

Troth J. Ethical and environmental labelling of foods and beverages. In: Advances in Food and Beverage Labelling. Elsevier; 2015:151-175. doi:10.1533/9781782420934.3.151

Wikström S, Jönsson H, Decosta PL. A clash of modernities: Developing a new value-based framework to understand the mismatch between production and consumption. J Consum Cult. 2016;16(3):824-851. doi:10.1177/1469540514528197

Wyrwa J, Barska A. Packaging as a Source of Information About Food Products. Procedia Eng. 2017;182:770-779. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2017.03.199

European Parliament. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft; 2011.

European Parliament. General Food Law. Published online 2002.

Dat N. Do the consumers take the environmental aspect into the evaluation of food quality? Published online 2021.

Carbon Cloud. Carbon Cloud Customer Lists.https://carboncloud.com. Published 2021.

Olof B. Different types of climate labels for food products. Published online 2009:71.