1. Introduction

In 2020, Việt Nam produced over 1.7 million kilograms of coffee, accounting for 16% of global production¹. While the story of how Việt Nam became a giant in the international coffee market has widely been studied and documented, the story of how coffee seeds were first planted in the land of Việt Nam often gets overlooked²⁻³. Thus, this article is written to tell the origins of a coffee plants in Việt Nam to fill the gap, intended to serve as a groundwork for future conversations.

2. Plantation of coffee in Việt Nam

Like other top coffee-producing countries, coffee was not a native plant in Việt Nam a few hundred years ago. In these lands, one could not separate the history of coffee from the bitterness of European colonization. In the 19th century, European powerhouses began to explore, claim, and exploit global lands. They used their power to enforce inexpensive labor in foreign lands to produce commodities for beneficial international trade and minor domestic needs. Accordingly, colonists often introduced varieties of sought-after crops to their settled and established lands to trial with prospective exploitations. In this story, France is the colonist, Việt Nam is the established colony, and coffee is the crop. Here unfold, the story dates back to the second half of the 19th century⁴.

At that time, Việt Nam’s territory and administration were not as unified as today. The government of the Nguyễn dynasty divided the land mass into three divisions from the north to the south — namely Bắc Kỳ, Trung Kỳ, and Nam Kỳ. Each region had its administrative systems with its customs and rules. Thus, the French conquered Việt Nam by reigning over each administrative head before taking absolute control with the establishment of French Indochine in 1887. This sounds like another European winning fight against Cerberus. But little did the French colony know that the living were the prisoners, and the dead were the valid owner of the tropical land. Opening the gate to the Underworld allows the dead to say to their worshippers, “this land is yours!”

Upon the colonial establishment, the French referred to the north and the south division of Việt Nam as Tonkin and Cochinchine, while they referred to the central division and Việt Nam as Annam. The French established their controls in different divisions at different times. Thus, coffee seeds arrived from different journeys — carrying different histories to be told.

2.1. Plantation of coffee in Tonkin

One year before the colonial establishment, the French took over Tonkin in 1886. They needed a man with a great depth of knowledge yet believed in the colonial policy to administer the vast exotic land mass. These requirements fit perfectly with Paul Bert — an extreme-left politician and concurrently a great professor of physiology. He was known for becoming the youngest France professor at 33 years old and for his remarkable scientific research. However, Paul Bert was also known for publishing ethnocentric textbooks with claims such as:

“The Negroes have black skin, hair curly like wool, prominent jaws, impressive noses, they are much less intelligent than the Chinese, and especially than the whites.”⁵.

Though his claim is deemed racist today, Paul Bert was a man the French needed in Tonkin at the time. On April 8th, 1886, Paul arrived in Hà Nội to officially receive the role of Resident General of Annam and Tonkin⁶.

To achieve the mission of colonial expansion, Paul Bert was looking for an explorer botanist. Through connections at the National Museum of Natural History, France, where he previously taught, Paul Bert was referred to Benjamin Balansa. At that time, Benjamin had previously explored North Africa and South America's botanical diversity and was looking for new adventures⁴. The agreement between the two was wired immediately, putting the exploitation of colonial lands and labor schemes into action.

After his arrival in April 1886, Benjamin spent months studying the botany of Tonkin — either by personal exploring or exchanging with botanists who preceded him there. In a letter to his fellows in 1887, he wrote:

“… The flora of this country is truly inexhaustible; I have been exploring Mount Ba Vì for more than a year and am far from having discovered everything. In none of my previous travels have I seen such a variety. On an equal surface area, Tonkin is certainly the country with the richest flora, especially considering the low height of its mountains. It's a beautiful country ….”

In the meantime, Paul Bert sent Benjamin to Java (Malaysia) to bring back coffee plants and quinquina. When Benjamin returned with unbeknown-to-him historical Coffea Arabica seeds, Paul Bert had already died of dysentery. The prospective plantations were nevertheless continued. Benjamin gave his collections to a few independent settlers inhabiting near Hà Nội for trial cultivation⁴.

Based on collected documents, between 1886 - 1887, the Borel brothers were the first to plant coffee seeds in Tonkin on the premise of Guillaume Freres under the foot of mount Ba Vì, Sơn Tây⁷. The action was followed by other farmers inhabiting across Red River Delta. In the following year, coffee seeds received meticulous care from colonial farmers, who not only settled themselves onto foreign lands but were also devoted to settling coffees and new plantations there. Coffee seeds grew, and coffee foliage eventually covered thousand of hectares across Tonkin by 1924⁸⁻¹¹.

2.2. Plantation of coffee in Cochinchine

As mentioned before, plantations of coffee linked with the settlement of the French military on Việt Nam’s territories. Across the map, Cochinchine was the first division that the Nguyễn dynasty to submit their authority to French forces, partly in 1862 and entirely in 1874.

While the introduction of coffee in Tonkin was well-documented with names and places, its stories of Cochinchine were much more indefinite. Nevertheless, the origins can be deducted from documents published more than a century ago, now archived in the digital space of the National Library of France, Gallica. Excerpts from the province’s annual reports, voyagers’ diaries, and exposition results revealed that coffee had been cultivated across the land more than a decade earlier than in Tonkin.

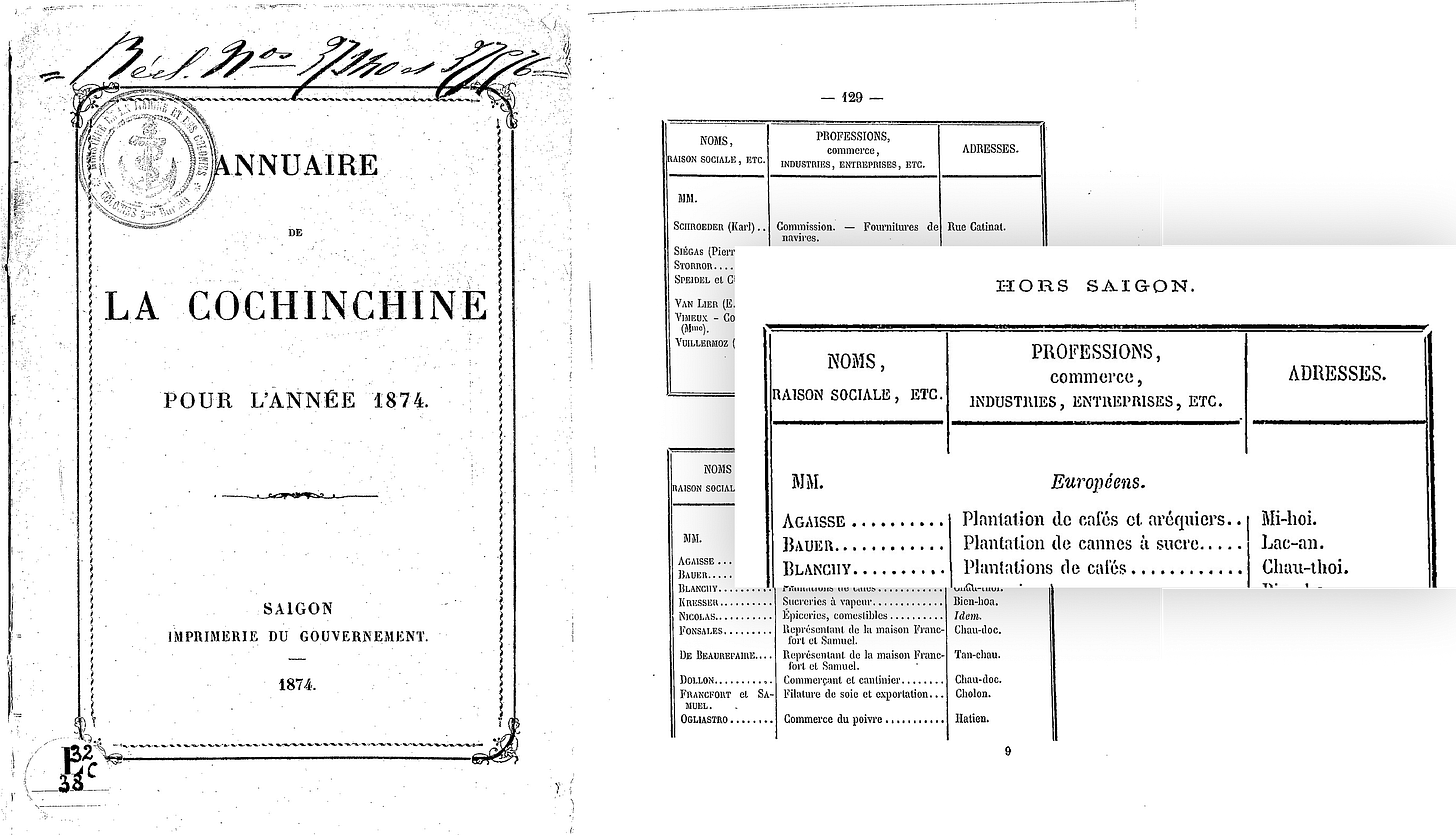

The Annuaire de la Cochinchine française from 1865 to 1888 is a valuable resource to start with. The annuals consist of all information related to French Cochinchina’s administration, from personnel working in administrative and commercial sectors to provincial expenses, population data, import/export stats, et cetera.

In the oldest archived annuals published in 1870 and 1871, searching for the keyword “café” results in the importations of 1272 coffee bags to Cochinchine, locations of 8 café shops across Sài Gòn, and most interestingly, a suggestion to cover hillside lands of Hà Tiên, Kiên Giang with a rich harvest of coffee, cocoa or quinquina. To be noticed, Hà Tiên is the province located furthest to the West of Sài Gòn, where Phú Quốc island belonged to¹²⁻¹³. By 1874, no land area was registered for cultivating coffee across 7 million hectares of Cochinchine. However, two monsieurs — Agaisse inhabited Mĩ Hội, Đồng Tháp, and Blanchy settled Châu Thới, Bình Dương — were registered in the annuals with the professions of “Plantations de cafés.”¹⁴. From these clues, two hypotheses for further investigation are: (1) official statistics on a coffee plantation in Cochinchine are dated from 1874 onward, and (2) coffee plantation experiments have been performed in Hà Tiên before 1870. These clues pointed the investigation toward another source of information — voyagers’ dairies.

Personal diaries are often considered unreliable sources of information. However, in the early days of colonization, many voyagers were civil servants or metropolitan entrepreneurs who traveled to Việt Nam to explore the colony. They wrote diaries to archive their observations and connected them with their prior scientific knowledge before compiling comprehensive reports about the new land. Their studies were considered critical documents for the French government to move forward with the colonization master plan. Among many other documents, two papers describing the status of Cochinchine before 1874 were deemed helpful in this investigation (1) Voyage en Cochinchine pendant Les années 1872-73-74, by a doctor, naturalist, and explorer Albert Morice and (2) La Cochinchine Française by J.-P. Salenave, a French trader in Sài Gòn.

An excerpt from Albert Morice’s stated that une vaste plantation de café already in total production in Tây Ninh in 1874¹⁵. As the plantation of coffee took at least 3 to 4 years to bear fruits, this suggests that the cultivation started around 1870-1871. This proves that the hypothesis about the lack of official statistics mentioned earlier is true because these coffee-cultivated lands were first reported on the Annuaire by 1878¹⁶.

Extractions from Salenave’s from 1873 directly removed the fog about the plantation of coffee in Hà Tiên before 1870. First, he observed that

“the soil of Phú Quốc offers the closest analogy to that of Manila and Java, and coffee plants from this last country imported into Cochinchina have perfectly succeeded and produced excellent products.”.

Salenave might not be the soil expert, Nevertheless, he made a point about the ongoing plantation of coffee in Phú Quốc at the time¹⁷.

In the same document, he presented his collected Cochinchine crop exportation statistics of 1867 and 1870. Total exports doubled from 33 million francs to 66 million francs within four years, portraying the colonial exploitation of foreign lands. Coffee was first exported from Cochinchine in 1870 but not in 1867.

From this information, my hypothesis for the origin of the coffee plantation in Cochinchine is either (1) first planted in 1867 because of 4 compulsory cultivating years or (2) a few years before 1867 with coffee consumed mainly within the province. Nevertheless, it is rational to conclude that coffee seeds were first planted in Cochinchine by French settlers from the early to mid-1860s.

2.3.Plantation of coffee in Annam

While the origin of coffee plantations in Cochinchine is hidden behind layered archival documents, the story from Annam was also vague but much more straightforward. On a trip to study the crops of Annam in 1914, the Deputy Inspector of Agricultural and Commercial Services H. Gilbert reported about the extensive cultivation of Coffea Arabica across Quảng Trị, mentioning typhoons and borers – Hypothenemus hampei – are the biggest enemies of the plant there¹⁸.

Nevertheless, Gilbert also pointed out the report from the memory of the vice resident of Quảng Bình, mentioning that a European priest brought coffee seeds and started cultivation around the 1860s there. Thus, the plantation of coffee in Annam perhaps as early as 1856, when the first French missionary arrived, looking for followers from Confucious land, or as late as 1867, according to the memory report.

3. Conclusions

Việt Nam is the second biggest coffee producer in the world, although coffee was not a native crop 200 years ago. Around the late 19th century, the French brought the beans there as part of their colonialization ambitions. Since the territory of Việt Nam was not as uniformly administered as today, the European powerhouse had taken control over different administrative divisions before setting up the colonial system over the whole land between 1862 and 1874.

Based on archived documents, it is inevitable that coffee beans arrived in the three different administrative divisions at three other times. Thus, the origins of the coffee plantations in Việt Nam are not a single story as told before. Chronically, coffee seeds were brought to Annam and Cochinchine around the 1860s. One was by a European priest, and the other by unknown French settlers. Almost 30 years later, in 1887, coffee seeds were first introduced and experimented with widely in Tonkin.

4. References

International Coffee Organization. Coffee Production Report 2020; International Coffee Organization, 2020.

Summers, C. How Vietnam Became a Coffee Giant. BBC News. January 25, 2014.

Fortunel, F. Le Café Au Việt Nam - De la colonisation à l’essor d’un grand producteur mondial; 2000.

Chevalier, A. L’œuvre d’un grand botaniste colonial méconnu : Benjamin Balansa. Rev. Bot. Appliquée Agric. Colon. 1942, 22 (249), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.3406/jatba.1942.1700.

Wikipedia. Paul Bert, 2022.

Joseph, C. Paul Bert Au Tonkin, 1887th ed.; G. Charpentier Et Cie: 13, Rue De Grenelle, Paris, 1887.

Léger, A. Lucien Levy et ses fils. Entrep.-Colon. 2020, 8.

H, C. L’Éveil économique de l’Indochine : bulletin hebdomadaire. LÉveil Économique Indoch. Bull. Hebd. 1924, No. 392, 32.

H, C. L’Éveil économique de l’Indochine : bulletin hebdomadaire. LÉveil Économique Indoch. Bull. Hebd. 1924, No. 391, 32.

H, C. L’Éveil économique de l’Indochine : bulletin hebdomadaire. LÉveil Économique Indoch. Bull. Hebd. 1924, No. 390, 32.

H, C. L’Éveil Économique de l’Indochine : Bulletin Hebdomadaire. LÉveil Économique Indoch. Bull. Hebd. 1925, No. 430.

Cochinchine. Annuaire de la Cochinchine française... (Saigon) 1870, 247.

Cochinchine. Annuaire de la Cochinchine française... (Saigon) 1871, 243.

Cochinchine. Annuaire de La Cochinchine Française... (Saigon) 1874, 255.

Morice, A. (1848-1877). Voyage en Cochinchine pendant les années 1872-73-74 / par M. le Dr Morice. H Georg Lyon 1876, 54.

Cochinchine. Annuaire de La Cochinchine Française... (Saigon) 1878, 296.

Salenave, J. P. F. La Cochinchine française. St.-Germain 1873.

Gouvernement Général De L’Indochine. Bulletin économique de l’Indochine Indochine française, 1914.

5. Extras

5.1. About the first registered coffee planters of Cochinchine

Little did we find out about MM. Agaissee across the Internet, nevertheless, MM. Blanchy was not a random peasant living in Cochinchine at the time. Paul Blanchy is from an upper bourgeois family in Bordeaux, where his father is a well-known merchant who participated in the international development of Bordeaux wine in the 19th century. He arrived in Cochinchine in 1871 and became president of the Colonial Council there in 1873 before becoming the first mayor of Sài Gòn from 1895 to 1901. One of the busiest streets in Sài Gòn nowadays – Hai Bà Trưng street – was once called Paul Blanchy street until 1952.

5.2. About the coffee plantation described by Albert Morice in Tây Ninh

From the description of Albert Morice, the location of the coffee plantation in Tây Ninh in 1870 was pointed out using the Plan Topographique of the province. The site was described as follows:

“… Le Jardin de l’Inspection, very beautiful and high, is built at the village entrance, on a hill a little lower than the fort, on the road to Bến Keo. Opposite her stretches a vast coffee plantation already in full swing. The Inspection is one of the most beautiful you can see….”

The description fits with the location of either Xóm Re Trên or the area between Xóm Rạch Re Dưới and Xóm Khương An on the historic topography. Nowadays, they are the land located next to Vàm Cỏ Đông River, belonging to either Trường Ân commune, Hoà Thành district, or Cẩm Giang commune, Gò Dầu district.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Khiếu Anh at Labo CIELAM, Aix Marseille for referring me to valuable resources in this. I also want to thank Frederic Fortunel at Le Mans Universite for sharing his book “Le café au Viet Nam” which I would recommend to anyone interested in the progression of coffee plantations in Vietnam since its origins. Lastly, this work can not be done without tremendous archiving job of people at BnF Gallica and enterprises-coloniales.